Low-pressure air systems are often introduced to make equipment gentler, safer, or more precise. Compared to conventional pneumatic setups, operating at very low pressures can seem inherently forgiving. The assumption is that if force is reduced, risk is reduced as well. In real industrial environments, the opposite is often true. As pressure decreases, tolerance for variation narrows, and control quality becomes far more important than raw capacity.

Modern industrial systems increasingly rely on low-pressure air for functions that influence outcomes rather than drive heavy motion. These include positioning, testing, surface processes, and instrument support. In such cases, air behaves less like a utility and more like a control input. Understanding how low-pressure regulation works, and why it differs from standard regulation, is essential for maintaining consistency, reliability, and predictable performance across equipment.

What low-pressure air regulation actually means in practice

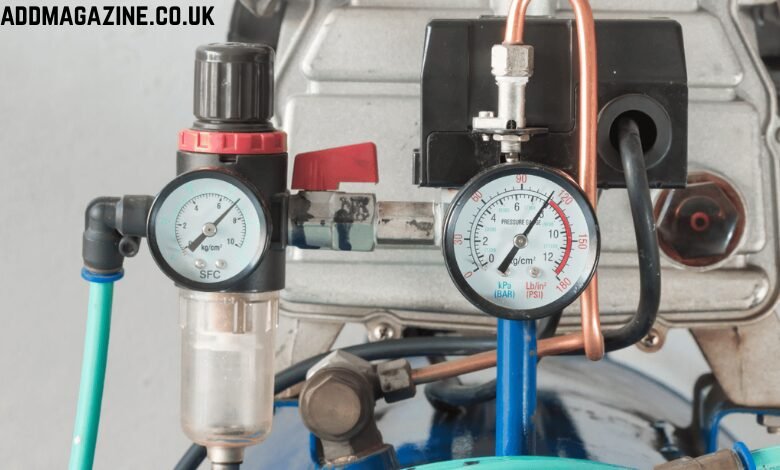

Low-pressure air regulation refers to maintaining stable and repeatable output pressure within a narrow operating range, typically between zero and five PSI, while responding smoothly to changes in demand. At these pressures, even small deviations represent a meaningful percentage of total output.

A Low Pressure Air Regulator 0-5 Psi overview is relevant in systems where pressure consistency matters more than airflow volume. These regulators are designed to control fine pressure changes without overshoot, lag, or oscillation—behaviors that are often acceptable at higher pressures but disruptive at low ones.

Why low-pressure control is more demanding than it appears

At higher pressures, inertia and stored energy tend to mask small fluctuations. At low pressure, those buffers disappear.

- Small changes have immediate functional impact

- Damping effects are limited

- Downstream components respond instantly

As a result, regulation quality becomes the dominant factor in system behavior.

How low-pressure regulators differ from standard regulators

Standard air regulators are built for durability and broad usability. They are designed to reduce pressure efficiently across a wide range, typically where output pressure is a small fraction of inlet pressure but still substantial in absolute terms.

Low-pressure regulators are designed around sensitivity rather than strength.

Design priorities shift at low pressure

Several internal design elements change.

- Springs are optimized for fine force resolution

- Diaphragm areas amplify small pressure changes

- Internal friction is minimized

In standard regulators, internal friction and coarse adjustment are acceptable because they represent a small percentage of output. At low pressure, those same characteristics become sources of instability.

Pressure stability versus pressure accuracy

Pressure accuracy refers to how closely a regulator can reach a target setpoint. Pressure stability refers to how well it maintains that setpoint when conditions change. In low-pressure systems, stability is usually more important than accuracy.

A perfectly set pressure that drifts under load creates more problems than a slightly offset pressure that remains steady.

Why stability drives performance outcomes

Stable pressure supports repeatability.

- Motion remains consistent cycle to cycle

- Measurements remain comparable over time

- Processes behave predictably

Instability introduces noise that spreads across systems and masks root causes.

Dynamic demand and low-pressure behavior

Industrial equipment rarely consumes air at a constant rate. Actuators cycle, purge flows pulse, and test systems draw air intermittently. At low pressure, response to these changes becomes critical.

Many regulators perform adequately at steady flow but struggle when demand changes quickly.

Common effects of poor dynamic response

- Pressure dips during actuation

- Overshoot after demand drops

- Slow recovery between cycles

These effects often appear intermittent, making them difficult to trace back to regulation rather than downstream components.

Startup behavior and transient pressure effects

When air supply is first applied, regulators must establish equilibrium between spring force and downstream pressure. Some designs overshoot the setpoint briefly before settling.

At low pressure, even short-lived overshoot can have consequences.

Why startup characteristics matter

- Thin membranes can rupture

- Lightweight fixtures can deform

- Sensitive assemblies experience shock loading

Low-pressure regulators are typically designed to ramp pressure smoothly to avoid these transient stresses.

Sensitivity to upstream pressure variation

Compressed air supply is rarely perfectly stable. Compressor cycling, demand changes, and distribution losses introduce inlet pressure variation. At very low outlet pressures, this variation can bleed through the regulator more easily.

Low-pressure regulators are engineered to isolate downstream pressure more effectively within their intended range.

When inlet conditions affect output

- Outlet pressure drifts despite steady demand

- Recovery time increases after upstream drops

- Control loops lose predictability

Understanding upstream behavior is part of effective low-pressure regulation.

Internal friction and hysteresis effects

At low force levels, internal friction becomes a significant factor. Seal drag, spring friction, and mechanical tolerances that are insignificant at higher pressures can dominate behavior near zero.

Hysteresis—the difference between increasing and decreasing pressure response—becomes more noticeable.

Operational impact of friction-driven behavior

- Dead zones where adjustments have little effect

- Lag between demand change and pressure response

- “Stick-slip” pressure behavior

These effects reduce repeatability and complicate tuning.

Typical applications that depend on low-pressure stability

Low-pressure regulation is most critical when air influences outcomes directly.

Common examples include:

- Precision pneumatic positioning of lightweight parts

- Leak testing and pressure-based inspection

- Thin material handling and assist air

- Controlled coating, drying, or purge flows

- Instrument air for low-range sensors

In each case, pressure variation directly affects quality or reliability.

Why low-pressure issues are often misdiagnosed

Failures caused by unstable low-pressure air rarely point directly to the regulator. Symptoms appear downstream, often in components that are reacting to pressure variation rather than causing it.

Patterns that obscure the root cause

- Pressure appears correct at rest

- Failures occur only during operation

- Replacing downstream parts offers temporary relief

Without observing pressure behavior under load, regulation issues remain hidden.

Pressure regulation in engineering context

Pressure regulators operate by balancing mechanical spring force against downstream pressure acting on a diaphragm or piston. Their behavior depends on sensitivity, friction, and flow dynamics. A general explanation of how pressure regulators function is provided in Wikipedia’s overview of pressure regulators, which describes how design choices affect stability, response, and accuracy across different operating ranges.

This context helps explain why regulators optimized for higher pressures behave poorly near zero.

Integrating low-pressure regulators into system design

Low-pressure regulators do not operate in isolation. Their performance is influenced by system layout, line volume, and downstream components.

Key integration considerations include:

- Placement close to the point of use

- Minimizing excess line volume

- Avoiding interactions with restrictive valves

Proper integration preserves regulator performance.

Testing and validation beyond specifications

Specifications rarely capture dynamic behavior, startup response, or sensitivity near zero. Bench testing under representative conditions reveals how a regulator behaves in practice.

Useful observations include:

- Response to rapid demand changes

- Pressure recovery time

- Repeatability across cycles

Early validation reduces commissioning risk.

When standard regulators are still sufficient

Standard regulators remain appropriate when:

- Operating pressures are moderate to high

- Output variability is acceptable

- Downstream components are robust

- Precision is not a primary requirement

Problems arise only when they are applied outside their intended operating envelope.

Reframing low-pressure air as a control element

Low-pressure air should be viewed as a control signal rather than a utility. This shift changes how components are specified and evaluated.

Precision, stability, and predictability become primary criteria.

Closing perspective: regulation quality defines system behavior

In modern industrial systems, low-pressure air regulation is not a minor detail. At pressures between zero and five PSI, regulation quality defines how equipment behaves, how processes repeat, and how reliable outcomes remain over time. Small variations upstream propagate into large effects downstream, often appearing as unrelated failures.

A regulator designed specifically for low-pressure operation aligns control behavior with system intent. It reduces variability at the source, protects sensitive components, and restores predictability. In low-pressure environments, good regulation does not add complexity—it removes it by preventing instability before it spreads through the system.