Most electronics don’t fail because the circuit “stops working.” They fail because the real world gets inside—or because mechanical stress slowly accumulates where the design never expected it. Moisture finds exposed copper. Condensation cycles in and out of enclosures. Dust and oil films become contamination. Vibration turns solder joints into fatigue points. Cable movement concentrates stress right at the connector pins.

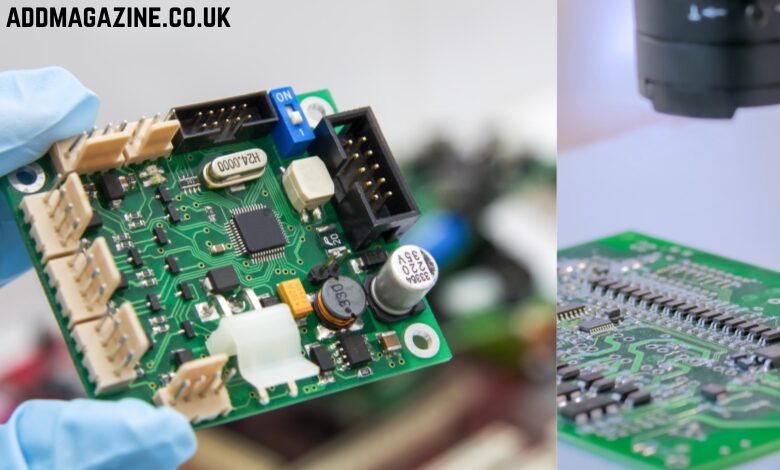

PCB overmolding has become a practical way to address these failure modes at the packaging level. In simple terms, a PCB (often together with a connector or cable termination) is placed into a mold, and a polymer structure is formed around it. The result is not merely “a covered board,” but a defined, repeatable geometry that can seal and support the most vulnerable zones—especially interfaces.

This article focuses on where PCB overmolding is most commonly used in real products, with an application-first view across automotive, industrial, and outdoor electronics.

What PCB Overmolding Means (Practical Definition)

PCB overmolding is best understood as packaging integration—and, more broadly, as a form of electronic overmolding: it combines protection, structure, and interface reinforcement into a single molded part.

- It often targets connectors, cable exits, and edge zones, not necessarily the entire board.

- It can create strain relief, sealing geometry, and mounting features in one step.

- It is typically chosen when reliability issues cluster around ingress paths or mechanical fatigue, not purely electrical design.

With that baseline, the most “best-fit” applications become clear when you look at how each environment causes failure.

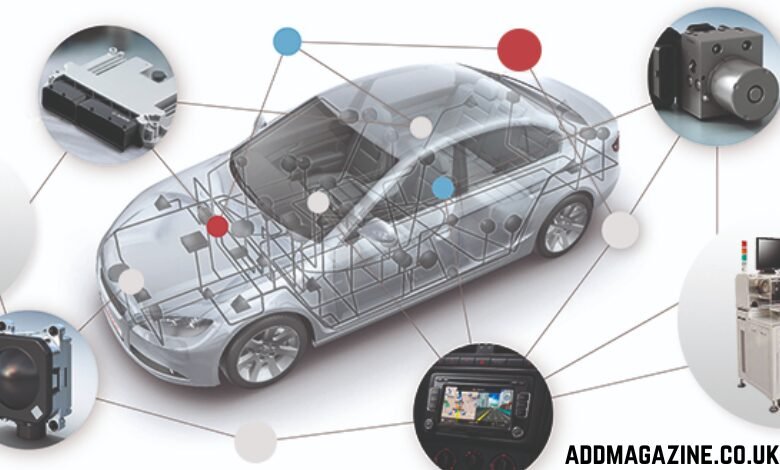

Automotive Electronics: When the Interface Is the Weak Link

Automotive environments stack multiple stressors at once: vibration, thermal cycling, splash water, condensation, road salt, oils, and cleaning chemicals. In practice, the failure origin is often not the center of the PCB—it’s the interface. Connectors get vibrated. Harnesses get tugged. Moisture finds its way into gaps near the connector or cable exit and starts corrosion or intermittent contact.

Overmolding makes sense here because it turns the interface region into a controlled structure. Instead of depending on a small solder joint plus a separate bracket/clip/adhesive step to handle loads, the molded body can carry the mechanical stress and reduce ingress paths at the same time.

Typical automotive modules where overmolding commonly appears include:

- Sensor modules, where a small PCB and connector are packaged into a compact, sealed geometry

- Body-adjacent subassemblies (for example, near doors, mirrors, handles) where vibration and moisture exposure are routine

- Lighting-adjacent interface pieces, where condensation and splash exposure are common

- Harness-related mini modules, where cable movement and strain relief dominate the reliability picture

What overmolding is usually “buying” in these cases is straightforward:

- Mechanical load redistribution away from soldered connector pins and pads

- Reduced ingress opportunities around the interface zone (where corrosion and intermittents often begin)

- More repeatable packaging compared with multi-part sealing stacks that depend heavily on assembly consistency

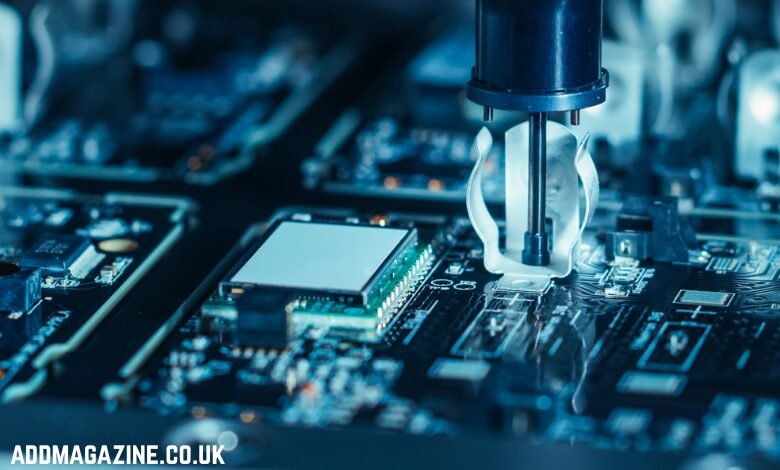

Industrial Electronics: Where Contamination and Fatigue Accumulate

Industrial electronics often fail quietly over time. The risk is not always direct water exposure—it’s dust films, oil mist, cutting fluids, debris, and continuous low-level vibration. When a PCB sits near a motor, pump, or moving mechanism, fatigue and contamination become long-term reliability drivers.

Overmolding fits industrial applications when the electronics need to behave like a component rather than a fragile assembly. By converting a PCB-and-interface into a structurally defined part, overmolding can reduce reliance on multiple sealing steps and reduce variation across production.

Industrial use cases that frequently benefit from overmolding tend to look like this:

- Sensors and encoders mounted near the process, exposed to dust and fluid contamination

- Operator-interface modules (buttons/indicators) that see repeated interaction and need stable packaging

- Edge subassemblies near vibration sources where long-term fatigue is the dominant risk

- Compact interface boards placed outside fully protected control cabinets for functional reasons

The value proposition in industrial settings is typically less about “waterproofing” and more about:

- Contamination resistance at interface regions that are otherwise difficult to seal reliably

- Fatigue resistance by transferring vibration loads into the molded structure

- Manufacturing consistency by simplifying packaging into a repeatable part geometry

Outdoor Electronics: Condensation and Time Are the Real Enemies

Outdoor products face a failure pattern that is often underestimated: condensation. Devices can be “sealed” and still fail because moisture repeatedly cycles in and out with temperature changes, forming condensation inside housings over months and seasons. That condensation drives corrosion, leakage currents, drift, and intermittent behavior—especially around connectors and cable exits.

Overmolding is commonly used outdoors to reduce the number of places where moisture can accumulate or ingress over time, and to harden interface zones that experience movement during transport, installation, or accidental impacts.

Outdoor best-fit applications commonly include:

- Outdoor IoT nodes and gateways that must run unattended with low maintenance frequency

- Lighting control or power interface modules exposed to weather and installation handling

- Field-installed monitoring devices in agriculture or infrastructure where long service intervals are expected

What overmolding typically solves outdoors:

- Fewer and simpler ingress paths (especially around cable exits and connectors)

- More stable interface sealing compared with tolerance-stacked enclosure joints

- Better robustness during installation and field handling, where drops and impacts are realistic

The Common Thread Across These Industries

Across automotive, industrial, and outdoor environments, overmolding appears most consistently when a product’s reliability is limited by a familiar set of packaging realities:

- The problem clusters around connectors, cable exits, and interface seams

- The product experiences vibration, pull, shock, or repetitive movement

- The environment includes condensation, contamination, or chemical exposure

- The design benefits from treating a PCB subassembly as a finished rugged component rather than something that needs additional protection engineered elsewhere

In those situations, PCB overmolding is not a cosmetic enhancement. It is a structural reliability decision.

A Quick Self-Check Before You Commit

A simple way to decide whether overmolding belongs in your design is to focus on failure origins:

- Are your field issues concentrated at connectors, harness exits, or edge zones?

- Do vibration, cable movement, impact, or thermal cycling show up in the operating environment?

- Is long-term stability more important than frequent servicing or upgrades?

If those answers trend “yes,” your product is aligned with the applications where overmolding tends to deliver the most value.

Closing Thoughts

PCB overmolding makes the most sense when electronics must survive as part of a mechanical and environmental system. In automotive modules, it stabilizes interfaces under vibration and moisture exposure. In industrial devices, it hardens packaging against contamination and fatigue. In outdoor products, it counters condensation-driven failure over long service lives.

When reliability depends on keeping the real world out—and keeping mechanical stress away from solder joints—overmolding is often the most direct way to make a compact electronic module behave like a rugged, repeatable component.